Is the Global Monetary Order Really Breaking Down?

Fiscal imbalances, trust erosion, reserve currency shifts, and the evolving role of central banks in a post‑fiat era.

Introduction

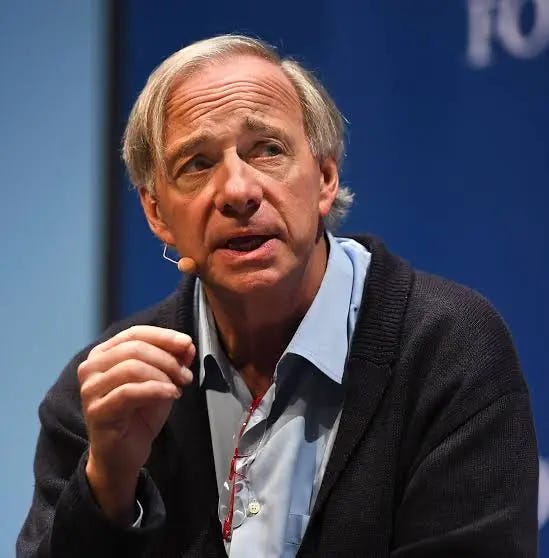

Billionaire macro investor Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, recently sounded a stark warning at the World Economic Forum in Davos: the current global monetary order is “breaking down” and fiat currencies and government debt are no longer being held by central banks in the same way they once were. His comments — amplified across financial news and social media — raise urgent questions about the future of money, sovereign credit, and global financial stability.

Dalio’s analysis taps into profound trends reshaping the world economy: rising debt burdens, shifting reserve behaviors, geopolitical tensions, currency diversification, and demand for alternative stores of value like gold. This article explores why Dalio’s warning matters, compares central bank behavior across key countries, and dissects the structural pressures on the global monetary system.

What Did Dalio Actually Say?

Dalio’s core point is simple yet profound: “fiat currencies and debt as a storehold of wealth is not being held by central banks in the same way” — meaning that central banks are reducing their reliance on fiat money and government debt as assets on their balance sheets.

He underscored this shift using two key signals:

Strong performance of gold and other non‑fiat assets relative to traditional sovereign debt.

A change in how central banks around the world allocate reserves, with less appetite for fiat government bonds as a primary reserve store.

This isn’t just an abstract macro claim — it speaks to deep trust dynamics in the global monetary system.

Why the Monetary Order Is Strained

1. Mounting Sovereign Debt and Fiscal Imbalances

Countries around the world have issued unprecedented piles of debt, especially since the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID‑19 pandemic. In the U.S., the federal debt has ballooned well beyond $30 trillion, and annual deficits are running into the trillions — creating concern about long‑term sustainability.

As debt grows larger relative to GDP, investors (including central banks) increasingly worry that:

Real returns on government bonds will be eroded by inflation.

Future currency debasement could occur through monetization (i.e., central banks buying government debt and expanding money supply).

Rising fiscal pressure could weaken confidence in long‑term sovereign credit.

Dalio and others see this as a core reason that fiat is no longer considered a safe “store of wealth” in the way it once was.

2. Eroding Trust Between Countries and the Dollar System

The current monetary order — sometimes called the Bretton Woods system of fiat currency dominance — rests on confidence in the U.S. dollar as the primary global reserve asset. That decade‑old framework assumes that countries will willingly hold U.S. assets (especially Treasuries) as a core part of their reserves.

But Dalio notes that this confidence is weakening:

“We know that both the holders of U.S. dollars … and those who need it, the United States, are worried about each other.”

Geopolitical tensions, trade policy disputes, and tariffs affecting global supply chains have compounded that trust erosion. Some countries are de‑risking their reliance on the U.S. dollar system — not necessarily abandoning it entirely, but diversifying reserve holdings and exploring alternatives.

3. Demand for Hard Assets and Gold

One of the clearest signals of the monetary order shifting is the surging demand for gold. Dalio highlighted that gold was one of the biggest market movers recently, outperforming even leading equity sectors.

Gold’s appeal comes from its:

Historical role as a store of value

Lack of counterparty risk

Perceived safety when fiat trust deteriorates

Central banks worldwide have increased gold reserves in recent years — not merely as a diversification from fiat currencies, but as a hedge against systemic risk and weakening confidence in sovereign debt markets.

4. The Threat of De‑Dollarization and Currency Diversification

Dalio’s warning also reflects rising discussions around de‑dollarization, where countries seek to reduce exposures to the U.S. currency and build alternative systems for trade and reserves.

For example:

BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) have discussed linked digital currencies and payment systems that do not rely solely on the U.S. dollar.

Emerging markets are increasing holdings of other currency assets and gold instead of Treasury bills.

Some central banks explore digital versions of their own currencies or alternative payment platforms.

These efforts do not signal an immediate collapse of the dollar, but they weaken its unchallenged primacy as the global reserve currency.

Comparing Central Bank Behavior: U.S., Europe, China, and Others

Understanding whether the monetary order is ‘‘breaking down’’ requires a look at how different central banks are behaving today:

United States — Federal Reserve

The Fed remains the dominant system anchor with its deep markets and status as issuer of the world’s main reserve currency. But actions such as balance sheet expansion and potential resumption of asset purchases have raised concerns about monetizing debt — meaning the central bank effectively finances government obligations through money creation.

While the Fed still actively holds Treasury debt and supports markets, Dalio and others worry that the combination of large deficits and monetary accommodation undermines long‑term confidence.

European Central Bank (ECB)

The ECB operates under a different mandate focused on price stability across multiple sovereign economies. While it engages in quantitative measures, the euro has not replaced the dollar as the dominant reserve currency. But the EU hasn’t aggressively expanded balance sheet holdings, and it continues to emphasize inflation control.

People’s Bank of China (PBoC)

China’s central bank behaves strategically:

It manages strict currency controls

It uses a managed floating exchange rate

It holds foreign reserves diversified beyond U.S. Treasuries

China has also increasingly added gold to its reserves, partly as a hedge against dollar dominance and external pressures.

Emerging Market and Other Central Banks

Many emerging economies are actively diversifying reserves:

Increasing gold holdings

Holding other currency assets

Exploring digital currencies and regional payment systems

These behaviors reflect a trend towards reserve diversification — a structural shift from decades of near‑exclusive dollar reliance.

Historical Context: How We Got Here

From Bretton Woods to Fiat Dominance

The last major realignment of the global monetary system came in 1971, when the U.S. ended the dollar’s direct convertibility to gold — a move known as the Nixon Shock. This effectively ended the old Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate regime, cementing the era of fiat currencies.

Fiat currency systems rely on trust in issuing governments and central banks, not gold convertibility. For decades, this model worked under conditions of broad geopolitical stability and expanding trade.

Post‑2008 Expansion and COVID Era Policies

Following the Global Financial Crisis and especially during the COVID‑19 pandemic, major central banks dramatically expanded assets and balance sheets to support economies. These policies, while stabilizing at the time, also increased sovereign debt burdens and monetary supply to historically high levels.

Is the Monetary Order Really Breaking Down?

Dalio’s warning is not that the system will collapse tomorrow, but that we are witnessing a structural shift — one in which:

The old trust configurations that supported fiat dominance are weakening.

Central banks are diversifying reserve assets away from pure fiat government bonds.

Gold and other non‑sovereign stores of value are gaining prominence.

Geopolitical tensions are accelerating reserve diversification and trade realignments.

This shift is gradual, but persistent — affecting portfolio management, fiscal policy, and international financial relations.

What Investors and Policymakers Should Watch

Reserve Currency Diversification: Continued growth in central bank gold reserves and non‑dollar holdings.

Debt Dynamics: Rising deficits and national debt ratios, especially in the U.S.

Geopolitical Risks: Trade disputes and capital repositioning influencing monetary trust.

Alternative Payments and Digital Currencies: Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and regional payment systems as part of post‑fiat strategies.

Conclusion

Ray Dalio’s assertion that the monetary order is “breaking down” reflects emerging tensions in global finance: rising sovereign debt, diverging reserve behaviors, geopolitical rivalry, and a waning dominance of fiat debt as a central bank reserve asset. While not predicting an imminent collapse, Dalio’s analysis signals a paradigm shift — one that could redefine money, credit, and trust across the global economy.

Whether this transition leads to a more diversified and resilient system, or to heightened instability, will depend on how policymakers and markets respond to these underlying pressures.

Affluent4casts provides in-depth analysis and informed perspectives on global financial markets and evolving financial microenvironments. Independent analysis — not investment advice.